Security Council Topic

| Security Council | Topic | Member states | Links and documents | Contact |

|---|

Managing Territorial Claims and Resource Competition in the Arctic

It’s nearly impossible to find a region which has seen a more sudden and profound deterioration of geopolitical stability than the Arctic. In the span of roughly a decade from 2014 to 2025, the Arctic transformed from a model region of international cooperation and an “exceptional” case to the pattern of great power competition, to a sui generis quagmire of destabilizing, corrosive, accumulating conflicts and grievances which are gradually spiraling out of control, stimulated by a series of overlapping international crises forming an almost intractable lock.

The Arctic has seen a substantial increase in warming as a result of climate change, between 2-4 times faster than the rest of the planet depending on the study, owing to the feedback/amplification effect caused by melting ice revealing the dark blue ocean to absorb more and more solar radiation which used to be reflected back into space by the white ice sheets. Decline in planetary reflectivity (albedo) has throughout Earth’s long history been a key tipping point leading to rapid warming, collapse of ice sheets, and changes in ecological balance. In the 21st century, these changes threaten to upend global socio-economic systems. The retreat of ice has allowed access to new trade routes connecting disparate continents and to untold riches in oil, natural gas, and rare earth elements, which are paradoxically of interest to both traditional energy industries and novel renewable energy efforts integral to transitioning away from fossil fuels. The Arctic contains 13% of the world’s untapped oil reserves and 30% of the untapped natural gas reserves, while rerouting trade from Europe to Asia north could yield reductions in travel times of up to 40% assuming the High North becomes passable for ships all year around. Given that the Arctic may see ice-free summers by 2030s, the day is fast approaching when we may also see megaports along the rim of Siberia.

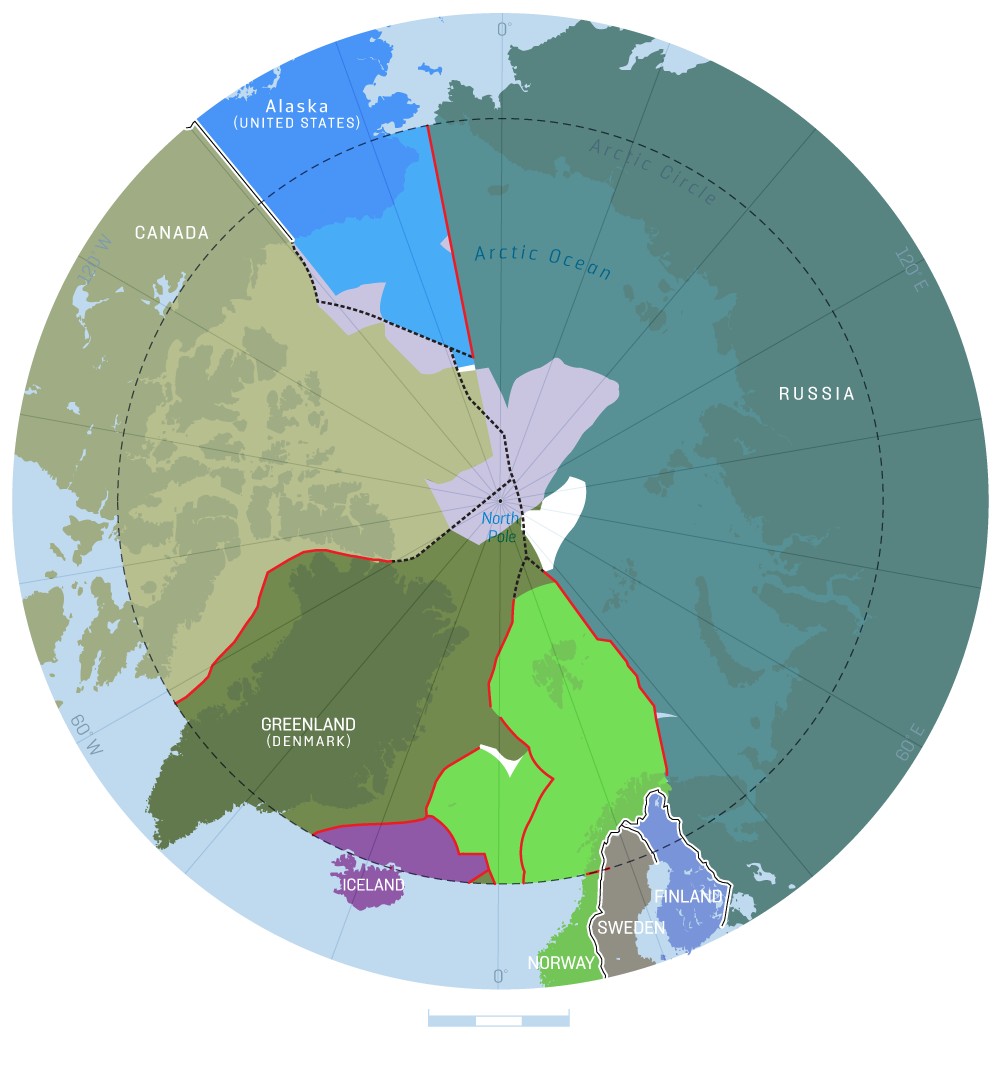

Unlike the Antarctic, which is governed by the special Antarctic Treaty System, the Arctic has instead been generally governed by codified and customary international law in general, namely by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Under the terms of UNCLOS, national sovereignty extends past coastlines through successive layers of dissipating rights. These are the territorial sea up to 12 nm (nautical miles) away from the coast, the contiguous zone up to 24 nm away, the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) up to 200 nm away, and finally the extended continental shelf (ECS) up to at least as much as EEZ but as further away as the shelf is found to extend under the sea. The rules are not always fully clear cut. The twin examples of the Northwest Passage and Northern Sea Route illustrate this perfectly. Canada maintains that the Northwest Passage connecting the Pacific and the Atlantic constitutes internal waters and is thus fully under its sovereignty, a claim disputed by the United States and other parties. Meanwhile, Russia has staked a full claim on the Northern Sea Route, a major shipping lane which falls within a loophole inside UNCLOS allowing countries greater control over such routes located in mostly icy seas, but the applicability of the said provisions allowing Russia exclusive control is contested given the melting ice.

In principle, UNCLOS rules allow countries to plausibly claim hundreds of nautical miles of high seas as their own. Since under the terms of UNCLOS, within their ECS, the state retains exclusive right to exploit minerals and non-living resources, extending control over the untapped riches of the Arctic has increasingly become a matter of high priority to the Arctic countries. The final limits of the ECS are adjudicated by the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) and multiple countries have sought to convince the commission of the validity of their overlapping claims. The efforts of the Russian Federation have been the most successful ones, as Russia convinced CLCS in 2022 that the Lomonosov Ridge, an underwater mountain lying 320-380 nm away from Russia proper belongs to Russia’s continental shelf. This finding has been heavily disputed by Denmark, which claims (via Greenland) ownership of similar seas. As determinations of CLCS are merely advisory and cannot resolve overlapping claims, a political process must do so. Nonetheless, Russia retains diplomatic leverage and momentum in this matter.

Existing international Arctic governance structures have found themselves incapable of keeping up with the exhilarating pace of changes. Traditionally, the Arctic Council, an intergovernmental forum and organization gathering all key stakeholders in the Arctic, played a key role in facilitating cooperation in the Arctic among the countries of the Arctic Circle, but the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 chilled the Council’s operations. Escalation of the conflict in Ukraine in 2022 caused a full breakdown of the Council’s usual operations, as 7 out of 8 members withdrew from active participation, all Western countries, opposed to Russian actions in Ukraine. Since then, cooperation has been reduced to strictly technical, low-stakes, barely keeping the lights on projects. In early 2023, Russia formally removed all references to the Arctic Council from state policy, replacing multilateral language with assertions of national interests. Later in the same year, the admission of Sweden and Finland into NATO in mid 2023 resulted in all 7 Western states on the Council being NATO members, further isolating the Russian Federation. The decline of the Arctic Council is particularly worrying owing to the fact it has been the primary means by which native populations of the Arctic have been able to articulate their needs and desires on the world stage.

Compared to Russia, the United States has found itself in a somewhat different position, owing to its extensive network of international allies, but limited legal backing for its actions. The United States refused to ratify UNCLOS in the 1980s over concerns unrelated to the Arctic, namely owing to UNCLOS establishing the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which was to be given the authority to grant permits for deep sea mining in high seas beyond all territorial claims, distribute revenue, and controversially, enable what American authorities saw as unacceptable forced technology transfers. However, as the Arctic grew in importance, industry and political pressure mounted internally and the US eventually acknowledged UNCLOS as customary international law, excluding ISA its deep sea mining rules. The US has since staked out its own continental shelf claims per UNCLOS rules, and in turn faced accusations of abuse by the Russian Federation and other parties of wanting to selectively benefit from UNCLOS insofar as it fits with its own national interests. For the longest time however, the issue of the Arctic and UNCLOS remained largely beneath the US public’s radar, being only a major concern for the authorities of the US state of Alaska and their representatives in Washington, and friendly oil industry lobbyists. Things changed sharply when President Donald Trump in 2019 announced an intention to acquire Greenland from Denmark. These comments were widely lampooned in the international community at the time, but they silently started a deeper process of re-evaluations.

The question of Greenland and its status has become a paramount one in Arctic politics. The world’s largest island is among the two last remaining pieces of the Danish colonial empire, along with Faroe Islands, and in recent years tensions between it and its mainland have been gradually escalating and boiling over at certain points. Colonized in the 17th century, and passing into the control of the Danish crown in 1814, Greenland was fully integrated into the Danish state in 1953, when the modern Constitution of Denmark terminated its status as a colony. Two referendums in 1979 and 2008 saw Greenlanders vote in favor of home rule and self-government, with Denmark today retaining control only over citizenship law, finances, security and foreign policy. Still, Greenland remains heavily dependent on Danish state aid. The relationship between Greenland and Denmark has suffered greatly over the years as the full extent of Danish state abuses in the 20th century driven by eugenics and racist ideologies came to light, including the infamous “Little Danes experiment” and the “Spiral case”. As part of the Little Danes experiment, in 1951 the Danish authorities conspired with the Red Cross and Save the Children to abduct 22 Inuit children to be “re-educated” as Danes in an attempt to “uplift” the native population of Greenland which was deemed to be inferior. The Spirals case refers to an ongoing investigation of state-sponsored sterilization of Inuit women by Danish physicians in the 1960s and 70s pursued with the goal of controlling and reducing the native Greenland population. Commentators have noted that these acts may constitute acts of genocide under the Genocide Convention, and Greenlandic politicians have openly accused Denmark of performing a genocide against the Inuit population. Denmark has strenuously denied these accusations and attempted to repair its relationship with its old colony by collaborating on investigations into wrongdoing and offering financial compensation. However, in 2025 it came to light that Danish local authorities removed a newly born child from a Greenlandic Inuit mother just one hour after birth, after she had failed the mandatory Danish “parenting fitness” test, despite previous Danish state legislation banning application of said tests on Greenlandic parents, which led to a wave of protests and new movements towards independence.

The year 2025 proved to be a major turning point in Arctic affairs for multiple reasons, a major one being the return of President Donald Trump to the White House and renewed claims against Denmark’s sovereignty regarding Greenland. Under the second Trump presidency, the US has pursued a series of very assertive, aggressive, and determined moves to undermine Danish position in Greenland, but these have thus far failed to fuel support in Greenland for joining the United States. Instead, they have further stimulated Greenland’s aspirations for independence and freedom from what is coming to be seen as colonial rule. The United States has framed its actions as a matter of national and international security, countering the rise of China and Russia in world affairs. While China formally lacks a stake in the Arctic, it has nonetheless positioned itself as a “near-Arctic state” seeking to benefit handsomely from melting ice and open seas by the means of a “Polar Silk Road”, furthering its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative meant to put Beijing at the center of global economic affairs.

The future of Greenland and the wider Arctic represent a major international issue of concern to all member states of the United Nations, as the Arctic stands at the nexus of painful histories and divergent possible futures which may lead to untold prosperity or acute devastation of natural habitats, loss of indigenous rights, and new wars threatening millions of lives.